Delftware vase made in London in the Chinese style. You can see the red earthenware clay peeking through the chipped glaze at the bottom.

In last week's post, I said that "Delftware potters referred to the work as porcelain: however, it was a cheap version of the Chinese pottery of the time." That got me thinking about why they were copying instead of using the real thing. Which led me to the history of kaolin, or China clay. The name kaolin is derived from Gaoling –Chinese: Gāolǐng; meaning 'High Ridge'. The name entered English in 1727 from the French version of the word: kaolin, following a Frenchmen's report on making Chinese porcelain. This prompted others to look for it.

When delftware was made (the 1600s), China was the only country to discover kaolin and realize its benefits. Let me remind you here that clay is mined from the ground; what a potter uses is called a clay body. Porcelain's body is composed of the raw materials of kaolin, feldspar, quartz, and ball clay (another light color clay known for its plasticity). Together they create three unique technical characteristics: hardness, whiteness, and translucency. In other words, it's non-porous, durable, and beautiful, making it perfect for dinnerware and tile. That's how kaolin is important to ceramics.

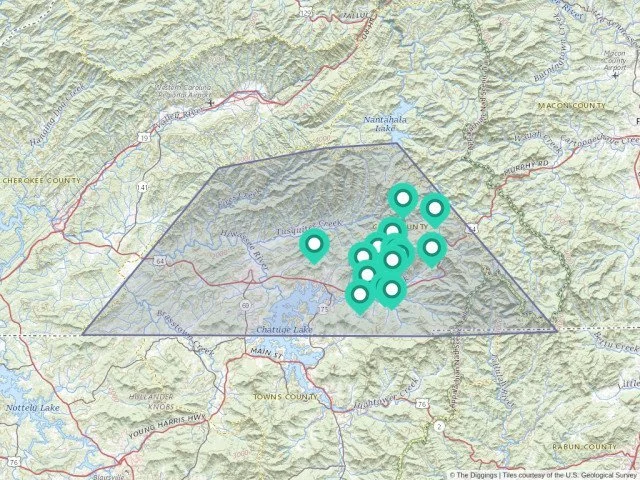

A kaolin mine in Georgia.